Recent Posts

THE STORY OF MY WILSON DISEASE: AGE 8 TO 53

By Barbara Noci I was born on the 6th of April 1972 in Empoli, a little city near Florence in [...]

Travis’s Story of Wilson Disease

Rare and Rural By Rhonda Rowland, WDA President We all love a small town. Images come to mind of holiday [...]

Newborn Screening for Wilson Disease

A 25-year dream coming close to reality By Alice Williams, WDA Communications Director Since the 1960s, the United States has [...]

Can Copper be Absorbed Through the Skin?

By Edward Tabor, MD, WDA Board Member The main source of copper for humans is food, and Wilson disease patients [...]

They Said “Yes” to Gene Therapy

By Rhonda Rowland, WDA PresidentWe continue the story of two trailblazers who are among the first Wilson disease (WD) patients [...]

Meet the Inaugural Gene Therapy Candidates

By Rhonda Rowland, WDA President The two gene therapy clinical trials for Wilson disease (WD) launched by Ultragenyx and [...]

The 100th Registry Participant

By Rhonda Rowland, WDA President

I’m study participant number 30 in the Wilson Disease (WD) Patient Registry. That’s not exciting.

However, if you’re participant number 100, you represent a milestone. And, that is exciting. Especially for those who’ve put in countless hours and tremendous effort to recruit patients, test them and analyze the data they’ve gathered, in order to glean new insights into a disease. The new findings are then published so they can be shared with other medical professionals, making it easier to spot new patients and give them the best possible treatment.

“This is extraordinary,” said Dr. Michael Schilsky, who leads the study and directs the Wilson Disease Center of Excellence at Yale University. “Few centers can boast such an excellent enrollment for patients with a rare disorder that continued to increase, even in the middle of a pandemic.”

While Yale hit the 100th study participant milestone, 50 additional WD patients have signed up at other study locations across the United States and Europe. The goal is to double enrollment to a total of 300 and follow them for five years. So far, participants range in age from birth to their 70s.

A name and a story behind every number

Behind every number representing a study participant, there is a name and a story. A story that, when it comes to Wilson disease, is often characterized by struggle, and then triumph, in finally getting a diagnosis for a series of bewildering symptoms.

Minh Vo is no exception. In 2019, he had an impressive career as a project manager at a boutique architecture and interior design firm near Grand Central Terminal in New York City. He commuted from his apartment in the hip neighborhood of Bushwick, Brooklyn.

Depression is the first symptom Minh recalls experiencing – that he now knows – was due to Wilson disease. At the time, he was in his late 20’s.

“The first physical sign that something was wrong was a high level of liver enzymes,” said Joseph Chiu, Minh’s cousin, who grew up with him and is the same age. He explained that the elevated liver enzymes showed up during a routine physical exam. Minh was then referred to a hepatologist, or liver specialist. “Interestingly enough, the hepatologist did a liver biopsy, but he didn’t do a full differential diagnosis, so he never tested for copper,” said Joseph.

Minh was misdiagnosed as having autoimmune hepatitis and prescribed steroids. Meanwhile, he went to a psychiatrist and therapist and was prescribed various antidepressants. None of them worked.

“I wanted to kill myself,” said Minh.

“At the time it was just so horrible for him,” explained Joseph, “because in addition to the depression, he was anxious all the time, having panic attacks and brain fog. His symptoms kept getting worse and worse. He was referred to a neurologist who did an MRI, and more treatments like TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation, were tried. None of it really helped.”

Within a few years of his first signs and symptoms, Minh lost his ability to draw, a necessity as an architect. He was drooling, couldn’t speak clearly and walked with difficulty. Experiencing this during the pandemic’s forced isolation only complicated matters. The primary specialists who should have thought of WD – a hepatologist, psychiatrist and neurologist – did not.

It was Minh’s older brother who figured it out. He’s a geneticist, so he hunted for an errant gene through genetic DNA sequencing. He found the faulty ATP7B gene.

“Minh’s brother said he had a 99 percent chance of having Wilson disease,” said Joseph. From there, the hepatologist referred Minh to an ophthalmologist who found the tell-tale Kayser-Fleischer Rings that signal WD, and confirmed the diagnosis.

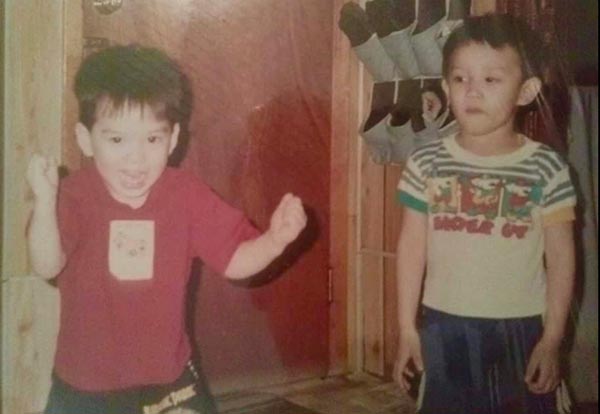

Joseph, age 3 and Minh, age 4.

“I was really happy,” said Minh, “because we finally had an answer and there were treatments.”

How the Patient Registry raises awareness

Minh is of Vietnamese descent. Could that have played a role in the delay of his diagnosis?

“If physicians remember Wilson disease from medical school, they may actually assume patients will be mostly Caucasian,” said Dr. Ayse Coskun, project director for the Wilson Disease Registry (WDR) based at Yale. “While there’s no clear research yet, the presentation of symptoms might be different among races. Our Asian participants all presented with extremely heavy neurologic symptoms.”

By publishing the WDR findings and presenting them at medical conferences, awareness is being raised for Wilson disease. Doctors have to think of WD in order to make the diagnosis.

“We are observing patients’ natural history of the illness,” explained Dr. Coskun, “and we now have a broad spectrum of patients – young and old – and when we have fresh data, we go to medical conferences and tell about it.”

Some of the fresh data collected from the initial two years of the study showed that half of adult WD patients have a major depressive disorder. The data also found that while both mental and physical health are impacted in WD patients, their mental health quality of life is worse than their physical quality of life. Findings also led to a new way of testing for “free copper”, which is used to determine a patient’s copper status.

Moving forward

Minh, age 24 and Joseph, age 23.

Once Minh had a diagnosis, his hepatologist referred him to Yale’s Dr. Schilsky for treatment. That was in the fall of 2021.

“Dr. Schilsky and his team were great at communicating a plan and what the expectations are,” said Joseph. “At no point were promises made. The prognosis is that you do get better. The only question is timeline, and you just have to be patient. Got to keep going with it.”

That’s where the WDR can help newly diagnosed patients like Minh. Patients need to be evaluated in all stages of treatment.

“By continuing enrollment – in particular newly or recently diagnosed patients – we are filling important knowledge gaps,” said Dr. Schilsky.

Moving forward in the WDR, critical information will be forthcoming on treating these patients and the best ways to monitor copper control.

One year later

A year after Minh’s WD diagnosis, he chose to enroll in the Wilson Disease Registry and became that milestone participant number 100.

“I want to try and help people,” said Minh.

“One of the biggest factors in the decision to participate is that we had such a frustrating journey to find the diagnosis,” added Joseph, whose been at Minh’s side throughout his journey. “The biggest selling point in this study was that we definitely don’t want others to go through the same thing we did.”

“Regrettably, the delay happened,” said Dr. Schilsky. “That is why it’s so important to keep the disease profile high – and to better understand the natural history of treatment in those found at even a later time when they are symptomatic.”

Minh’s depression has lifted. And, he says his anxiety is gone.

“A year ago I didn’t see Minh’s charming smile,” recalls Dr. Coskun, who met him when he first came to Yale for an evaluation and begin treatment. “Cognitively, he has improved a lot. Even his handwriting has improved. He participates more in the decision-making process for his own care. It’s amazing, but at the same time he has a long way to go, but hopefully we’ll get there gradually.”

Joseph lives just minutes away from his cousin and has seen Minh make huge strides over the past year.

“He’s actually able to speak audibly now where before it was hard for him to string a few words together, think of the words and formulate them,” recalls Joseph. “We were shooting basketballs around the other day and he wouldn’t have been able to do that even a few months ago because he’d have issues standing.”

As a physical therapist assistant, Joseph knows where to challenge his cousin.

“I’ll say things like ‘bring your knees up and work on flexion,’ or ‘you’re having a drop foot, make sure you’re working on dorsiflexion.’” He’s not just his cousin’s advocate in his healing journey, but also holds him accountable. “Just like my regular patients, when Minh admits to not doing his exercises I’ll say ‘c’mon man, I’m not asking for much.’”

Still to come

Minh is now 32 and has goals to reach, hobbies he intends to return to — Muay Thai, also known as Thai boxing, which is a combat sport that uses a combination of fists, elbows, knees and shins. He also wants to get back to playing basketball, running and hiking.

While Minh isn’t able to work yet, he plans to return to his job at Ascher Davis where his boss is kindly holding it open for him.

And Minh is already making a difference for others with WD. If you’re in the WDR study, and whether your assigned number is 30 or 100 – exciting or not – the data you contribute matters. It’s helping others with Wilson disease, and will hopefully help those yet to be diagnosed, have an easier story.

If you or a family member would like to participate in the Wilson Disease Registry, please contact (203)376-6043 or email wd.registry@yale.edu.

WDR Locations:

Yale University, New Haven, CT

Advent Health, Orlando, FL

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle WA

University of Heidelberg, Germany

Atrium Health Wake Forest, Winston-Salem, NC